-

#647 – Cyborg (1989)

Cyborg (1989)

Film review #647

Director: Albert Pyun

SYNOPSIS: In the near future, the world has become a post-apocalypse wasteland, and a ruthless gang is terrorising what is left of the United States. A female cyborg is sent to retrieve data from New York City and return it to Detroit in order to finish the development of a cure for a plague that is killing the survivors. She runs into a man who is fighting the leader of the gang, and asks him to escort her to Detroit…

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: Cyborg is a 1989 sci-film. Set in the typical post-apocalyptic wasteland of Mad Max ripoffs (and post-nuclear America too, I suppose), a plague is ravaging the survivors, and scientists in Detroit send a cyborg to New York City to get data that can help them complete a cure. While there, a gang tries to capture her so they can control the cure, and she seeks the help of Gibson Rickenbacker to escort her back to Detroit. The whole setup is very typical of this type of film, with the lone lead character who has abandoned his humanity rediscovering it as he is forced to accompany other people on a dangerous quest across the wasteland. There’s nothing that really sets the film apart from the oh so many similar films of the time. There’s some decent action that mostly revolves around Van Damme’s kickboxing expertise, but it’s all fairly par for the course.

In a film where one of the main characters is a cyborg, Van Damme still manages to come off as the last human character: his line delivery is barely audible, and clearly struggling with speaking English at some points. The villain is just your typical unhinged psychopath that doesn’t offer anything interesting, and everyone else is equally as dull. There’s some decent practical effects with the whole cyborg, but nothing too remarkable. The film really fails to embrace its best aspects: the fight scenes, and too much stunted dialogue upsets any sense of pacing. Probably not the worst of these types of movies, but Cyborg fails to really offer anything interesting, and doesn’t capitalise on the few things it does competently.

-

#532 – Lobster Man from Mars (1989)

Lobster Man from Mars (1989)

Film review #532

Director: Stanley Sheff

SYNOPSIS: A movie studio executive is plagued by money problems, and requires a tax-write off to keep the IRS away. He decides to produce a film brought in by a young film writer that is utterly absurd: “Lobster Man from Mars…”

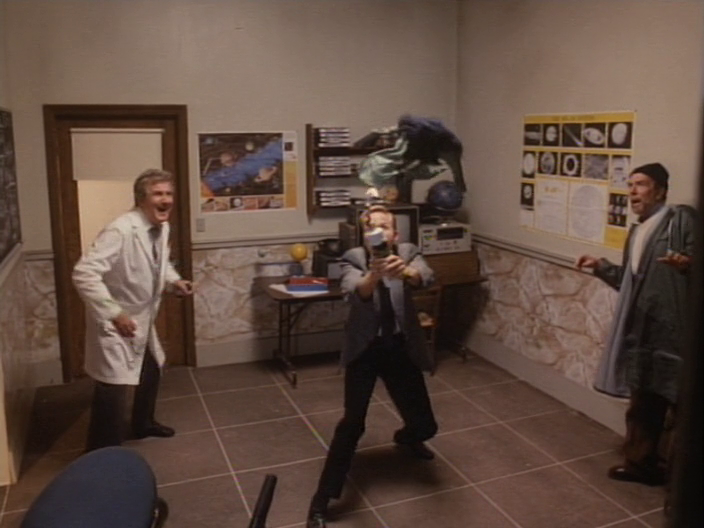

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: Lobster Man from Mars is a 1989 sci-fi film within a film. Opening up, we see Movie mogul J.P. Sheldrake, who is facing monetary pressure from the usual suspects: his ex-wife, the I.R.S., and so on. He decides he needs to release a movie that flops so badly he can make it a tax write-off and keep those he owes money to at bay. Fortunately, young movie writer/producer Stevie Horowitz walks in with the perfect potential film: Lobster Man from Mars, a film in the style of the old b-movie sci-fi films. The film (as a whole) becomes a film-within-a-film: The movie mogul sits in a theatre to watch the “Lobster Man from Mars” film, and we watch it as well, with a few occasional cutaways to Sheldrake to offer his thoughts. It’s an interesting setup, but was done prior in the 1968 film The Producers to much better effect. We’re also only taken out of the film a few times to see Sheldrake’s thoughts, meaning for the most part the “film in a film” element is irrelevant. With regards to the “Lobster Man from Mars” film itself, it follows a very typical b-movie sci-fi plot which it is aiming to parody: Mars is “leaking air” from it’s atmosphere, and so the ruler of Mars sends the dreaded lobster man and his assistant Mombo, who resembles a gorilla in a space helmet, to go to Earth and steal all it’s air…? Honestly, I’m not sure how they’re going to steal Earth’s air, and how it’s going to help if Mars is “leaking” any air it gets anyway, but regardless, when they arrive on Earth, the killing starts, and anyone who gets in their way gets turned into a pile of bones.

The film mostly plays it straight, with the film-in-a-film just being played without any commentary or over-the-top parody: it could easily pass for an actual b-movie. This is both a core strength and a weakness in the film: the best comedic moments come from the film playing it completely straight without any overt humourous moments, and it is the unexpected moments that provide the best comedy. The drawback to this is that it sometimes plays it too straight, and you forget you’re watching something that is supposed to be funny for fairly long stretches. The humour also feels fairly niche, in the sense that you would have to have actually watched these films originally to really get what it is parodying. Some of the really niche references, such as Colonel Ankrum being a reference to Morris Ankrum, who played similar characters in 1950′s films, is only going to be understood by a fraction of viewers. It definitely gets the b-movie feel right, but in 1989, there was plenty of other parodies of the genre that offered something new and entertaining from an entertainment perspective. This film just feels like it goes through the motions while reminding you it is a parody from time to time. There were a few of these b-movie parodies in the 80′s, but they typically went for a more upfront comedy and absurd premise, such as Killer Klowns from Outer Space. While a plot about Mars leaking air sounds quite silly, it definitely fits the b-movie mold, and would probably have fit right in. Although released in 1989, the film was actually written about ten years earlier, and it definitely feels that way. Lobster Man from Mars does something a little different, but it altogether feels a bit too niche and relies too much on in-jokes to appeal to a more general audience.

-

#481 – Hard to be a God (1989)

Hard to be a God (1989)

Film review #481

Director: Peter Fleischmann

SYNOPSIS: On an alien planet much like Earth, a society is undergoing a period of oppression similar to that of the middle ages of Earth. A group of scientists have been sent to observe this society, and study this event as it unfolds, with strict orders not to kill. Richard, one of the scientists, heads into the city of Arkanar as an observer, but he and his fellow observers find that staying out of the troubles of the inhabitants is more difficult than anticipated, and brings them face-to-face with emotions and feelings that humanity itself has lost…

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: Hard to be a God is a 1989 science-fiction film based on the 1964 novel of the same name. The film is set in humanity’s future, on an alien world where the civilisation is undergoing a period similar to Earth’s middle ages, and the rulers are cracking down on any inventors, artists, or scholars which may result in society moving into a Renaissance-era progression of society. In orbit above the planet, a human ship observes the settlement of Arkanar, and monitors a group of observers they have sent down to the planet. One such observer, Richard, takes on the identity of Rumata, a nobleman who was unknowingly to the citizens of Arkanar killed some time ago. With this identity, Richard/Rumata is able to observe a lot of the city freely, and also attempt to safeguard the scholars etc. that are being hunted. The plot centres around “Rumata” as he mingles in with the various residents of Arkanar; from the royal court to the common man, and the plot hinges on Richard becoming aware that it is impossible to remain neutral or observant when he is covered in the dirt of the city and the unguarded emotions of its people. The film proceeds very slowly through this scenario, and it is a very simple one that fills the two hour runtime by slowly immersing the viewer in the mess of the world that the humans are sent to observe. It is difficult to follow at points, but also that seems to be the point; that the struggle of daily life on this planet doesn’t neatly resolve itself into a smooth narrative.

Unlike the 2013 adaptation of the novel, here we get a glimpse of the spaceship and the state of humanity. It seems that humanity has “evolved” to a point where it has risen above the feeling of emotions, and as such look down upon the state of Arkanar as primitive and very much behind them as a society. As the film progresses, some of the scientists, who watch through a video feed implanted in Richard’s eyes, begin to feel emotions they have never experienced. It’s not the main focus of the film, but it is a neat little touch that shows how being a detached observer, as a human being, is not as easy as deciding to throw away your emotions, and that they always have the possibility of returning without control. The characters become familiar and involved with the story as the viewers do, and so when it is time for them to get involved beyond the observer role and help out the people they have lived among. I wouldn’t say it pulls this off in a perfect way, but it does enough to build up the story and setting to make this pay off. There’s some characters which don’t have that serious tone and “feel” like particular characters (the King, for one), and so I’m left wondering just how serious a viewer will take the film with some of these very stereotypical character tropes and bizarre hairstyles.

Production-wise, the film is fairly well put together: Arkanar has a distinct look and feel to it, even if its aesthetics of being shot in a desert seem very reminiscent of a lot of other films. The sci-fi elements are not the main focus, but the props and sets we do see are serviceable, if unremarkable (again, they are not the focus, so this is a good thing). With regards to making the environment look like a dirty, medieval setting, there’s effort put into getting the scenes and props right, and there’s a certain level of dirt but it does feel a bit uneven. Sometimes everyone is a bit too clean, and there are some moments when the gore comes out of nowhere and instantly unsettles the mood. I can think of two such instances: a decapitated head, and one part where a live pig is cut open and killed. I really hope that pig was a prop, but it definitely looked real…anyway, maybe I may be judging it a little harshly in this regard because the 2013 version does such an elaborate job in making the film visceral and filthy that this version can only look bad by comparison. The soundtrack, with it’s synth-heavy sounds, definitely places it in a certain moment in time, and while it’s not bad, it certainly ages it. Overall, Hard to be a God is a fairly average film with some stand-out and memorable moments, but they are few and far between across the two-hour runtime, and the plot ultimately fails to put down roots to dive the film direction and purpose. Not a bad film, but in terms of fitting the mould of cinema, it’s going to be a bit difficult for some viewers to get into.

-

#474 – A Visitor to the Museum (1989)

A Visitor to the Museum (1989)

Film review #474

Director: Konstantin Lopushanky

SYNOPSIS: In a seemingly post-apocalyptic world, a man visits the shoreline from the city to visit a museum that is only accessible one week every year when the tide is low enough. He is following the rumour that somewhere inside is a portal to another world, where one can escape the hell that is the one he lives in has become…

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: A Visitor to the Museum is a 1989 soviet post-apocalypse film directed by Konstantin Lopushanky. The film is set sometime after an unspecified ecological disaster has ravaged the planet: many people have become mutants and are locked up in reservations to be used as slave labour and such, while what remains of the unmutated live in cities. We aren’t given too much detail on the state of the world or what happened to it, but the backstory isn’t really important: like a lot of post-apocalypse films, how the world ended doesn’t mean much when you’re just trying to survive day-to-day in a new harsh world. A man visits the coast from the city hoping to visit a museum of relics from the old world buried beneath the sea. The path to the museum is accessible only once a year when the tides are low enough, and the man is following a rumour that within the museum is a portal to another world to escape the horrors of the one he currently lives in. The story of the film is very abstract and never hinges on definitives: a lot of the plot is casually explained as the man has tea with the family he is staying with, and they talk about the state of the world as very much matter-of-fact, in contrast to the true hell that the mutant “degenerates” are constantly experiencing.

Konstantin Lopushanky, the director of this film, worked on Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker film, and it definitely shows: the themes of isolation and desolation in a post-apocalyptic world and trying to find a way out are shared between the two, and there are very similar camera techniques and effects used to convey this. Lopushansky, however, always feels like Tarkovsky’s apprentice, and never really surpasses the master that is Tarkovsky, or offer anything different. The weak links in the film are definitely how the story reveals itself, and offers very little direction or clue to what is going on. Obviously, the film is meant to be ambiguous and centres around a loss of meaning in the post-apocalypse, but the film feels a bit too ambiguous in centring the main character and certain aspects of the film so you never know where they are or what’s going on. The plot points that do offer something include the contrast between the unmutated, who are unbothered atheists, and the God-fearing “degenerates” who scream out bible verses and quotes, even though none of them know what any of it means because the meaning of the bible has been lost.

The production of the film feels very considered, and again obviously taking inspiration from Tarkovsky. The outdoor location shots looks great, particularly the mountains of garbage and rubble that our protagonist traverses, which is apparently what most of the world looks like now. The landscape shots that emphasise the isolation of the protagonist abandoned amidst nature also works well. There’s also the large crowds of mutants in certain scenes give off an eerie feeling, as they move and act in seemingly genuine terror. Lopushansky uses the colour red to completely light many of the scenes, and it provides a good bit of consistency throughout.

This is definitely not a feel-good film: it is the end of the world, and we’re meant to feel it, the only hope of escape is this absurd rumour the protagonist is chasing about a portal to another world, which as the only option, shows just how bad things are, but again the unmutated just sitting around and discussing over tea as just a simple matter-of-fact furthers that strange contradiction. Overall, Visitor to a Museum definitely tries to capture some of that Tarkovsky magic of slow, epic films, but it never really hits the mark completely, nor does it offer anything new or original to the Tarkovsky formula. It’s not a bad film, and it received some decent recognition and awards, but again falls short of the master due to leaving things too ambiguous and without direction.