-

#338 – King Kong vs Godzilla (1962)

King Kong vs Godzilla (1962)

Film review #338

dir. Ishirō Honda

SYNOPSIS: Pacific Pharmaceuticals are having trouble coming up with some successful advertising. Mr. Tako, the head of the company, is told about a monster that exists on a remote island, and sends Sakurai and Kinsaburo, two of his employees, to capture it so he can use it as the new mascot for the company. However, another monster appears: Godzilla is back and goes on the rampage, and a plan is devised to bring Godzilla and this new monster, King Kong, together in the hopes they destroy each other before they destroy everything else…

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: King Kong vs Godzilla is a 1962 monster film and the third film in the Godzilla series. Given that King Kong is a Hollywood character, and Godzilla a product of Japanese cinema, this film is a true crossover of east vs west. The film starts off showing the failed marketing of Pacific Pharmaceuticals, and their boss Mr. Tako tearing his hair out trying to get attention for the company. A doctor tells Mr. Tako about a remote island in the South, where an indigenous tribe worships some kind of monster. Mr. Tako somehow concludes that getting this monster to advertise his products as a mascot would lead to the company dominating TV ratings, and so sends to marketers Sakurai and Kinsaburo to the island in order to capture the monster and bring it back to Japan. This monster turns out of course, to be King Kong, and the opening act of the film focuses on his origin story. It’s pretty similar to earlier incarnations in that King Kong is worshipped as a God by an indigenous tribe, who make various offerings to him. The film slowly builds up to his appearance then engages in a fight scene with a giant octopus (really just a regular-sized octopus on a model set), which establishes King Kong’s strength and showcases his power before the inevitable meeting with Godzilla. It doesn’t add much to the character of King Kong, but it doesn’t need to: some characters just don’t need to be more complex or have a motivation to smash stuff.

When King Kong is sedated and on the way back to Japan, Godzilla awakens from being trapped in ice, and heads off on the rampage. The Japanese Self Defense Force tries a number of operations to try and stop it, but all of them fail. The only option left to them is to get King Kong and Godzilla to meet and destroy each other. It should be noted that the whole tone of this film is a lot lighter than the previous two Godzilla films. The story being based around using these monsters in a war for TV ratings shifts the focus from the horrors of the destruction to more of a satirical look at human’s and corporation’s response to tragedy to use it to maximise attention and ratings. This ultimately makes the film a bit more goofy and silly than the original two films, which were very dark, and had powerful messages about Japan’s relationship to destruction and nuclear technology in the aftermath of the Hiroshima bomb. It’s not a bad move that the film takes, it’s just something different, and it is the direction the film series takes after this one to appeal more to younger viewers. Again, we get the basic plot points of King Kong condensed into this film, with him being captured, breaking loose, and going on a rampage in a city, while kidnapping a woman and climbing a tall building. The people that made this film clearly wanted to tell King Kong’s story in full, but also in their own way, making him feel almost at home in the setting of Japan, by which I mean trashing their cities…

When we eventually see King Kong and Godzila face off, Godzilla manages to overcome King Kong easily thanks to his atomic breath meaning King Kong cannot even get close. In their second meeting, King Kong fares better thanks to having absorbed electricity form power lines and an oncoming lightning storm: it is hinted that King Kong has the ability to summon storms and has an affinity with lightning, but it’s not explained very well. So while King Kong eventually emerges the winner in the end, Godzilla gets a victory as well, so it should satisfy both fans. Apparently King Kong was even more popular than Godzilla in Japan at the time, so having him win at the end obviously satisfies more people. The monsters are played as in previous Godzilla films by men in suits rampaging over model sets. The suits look decent, and the fighting is carefully choreographed, but does get a little silly at points, such as when they’re throwing rocks at each other. Some of the plans to deal with Godzilla are very cartoon-ish too, such as literally digging a pit and covering it up, so that Godzilla will fall down into it. Also airlifting King Kong by tying balloons to him looks pretty silly.

This is the first time we have seen Godzilla and King Kong in colour, since their previous films were in black and white too, and the addition of colour definitely makes them look less threatening anyway. One thing that stands out is Godzilla’s big eyes that are almost cartoon-like, whereas King Kong looks extremely messy and primal, which sets up a good contrast between the two. The effects are pretty decent, but there’s not as much destruction as the previous films, probably because over half the film’s budget went to securing the rights to use King Kong in the film. Overall though, while it is a little different in tone to previous Godzilla films, it changes things enough to keep it fresh, and is structured well to tell the story of two monsters alongside giving ample screen-time to both. Some people may not like the goofy human stuff, but all in all it’s a decent offering.

-

#337 – Marvel’s The Avengers (2012)

The Avengers (2012)

Film review #337

dir. Joss Whedon

SYNOPSIS: While S.H.I.E.L.D. is performing experiments on an object known as the tesseract, a potential source of unlimited energy, it is stolen by Loki, a demi-god who wishes to use it’s power to subjugate the human race. Nick Fury, the director of S.H.I.E.L.D., assembles a team of heroes to counter this new threat to Earth, but first they must learn to work together before they can take on Loki…

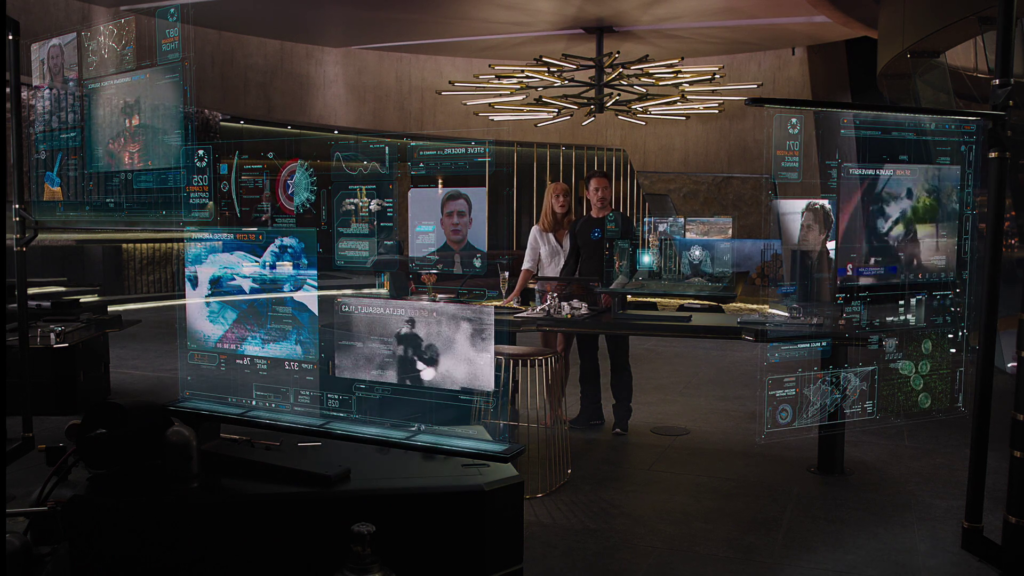

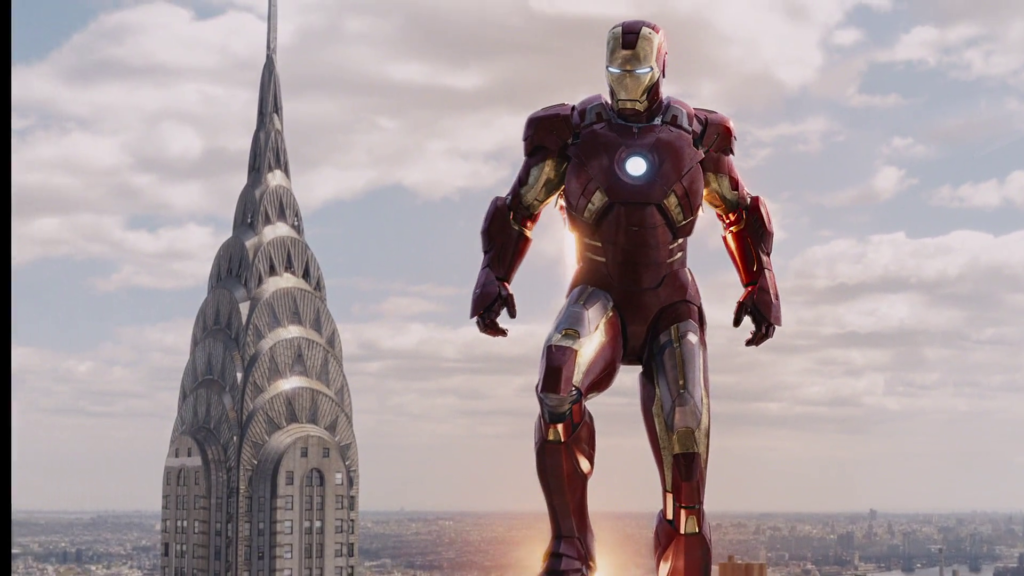

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: The Avengers (or Marvel’s The Avengers or Marvel Avengers Assemble) is a 2012 superhero film that is the culmination of the first series of films establishing the marvel cinematic universe. The previous films mostly dealt with the origins of the characters, while also providing hints about how they will fit into the wider universe. This film has the aim of bringing all these different superheroes together, with their own unique presence, powers, and personalities, and devising a way for them to work together as a team. It is certainly an ambitious project to cross-over all these different worlds and stories, requires a balance to get right with regards to using each character effectively.

The film starts off showing the S.H.I.E.L.D. agency conducting experiments on an object called “the tesseract”, which played a part in the Captain America film and briefly shown in the Thor film. They are trying to harness its power to produce a limitless source of energy. It suddenly springs to life and opens up a portal through which Loki, the antagonist from Thor, emerges. He takes control of the minds of a number of personnel, and escapes the facility with the tesseract. Nick Fury, the director of S.H.I.E.L.D., recognises the severity of the situation, and calls upon the various heroes to track down Loki and the tesseract. The film introduces each of the characters individually, so they are each explored on their own terms and their personal motivations are established firmly. The story structure is fairly standard, with a clear three-act structure that flows as you would expect, but there’s plenty of humour, action and story packed into them that the film nevertheless gives you everything you need. With a runtime of nearly two and a half hours, it’s a long one, but every scene is worthwhile in some way, and it could have probably got away with being even longer because there is so much potential with these characters and setting.

The characters have already been established through the previous films, primarily dealing with their origins and motivations that make them heroes. Even if you haven’t seen all of them, you get a pretty good idea of who they are and what drives the. Captain America comes across a heroic soldier who comes up with a strategy for battle, Iron Man/Stark is the guy with the resources who deflects criticism with his humour. Banner/The Hulk is the smarts who is also an unpredictable element, and Thor is a demi-God out to stop his Brother. Black Widow/Romanoff and Hawkeye/Barton did not have their own films, but appeared in the others so they are somewhat established, but Romanoff especially gets a lot to do in the film to firmly develop her role in the group. Each of the heroes is a big personality, so initially have a hard time finding their feet working together in a group, and it’s fun watching everything come together. The death of agent Coulson, who played a big part in bringing everyone together, is an emotional scene that gives everyone motivation to work with each other, and gives the team a unifying purpose. I think the only character that could have done with more development is Loki, whose motivations are a bit muddled, and his role in a larger scheme is left very ambiguous. In one sense, it works because Loki has a specific goal (to rule Earth) and is a simple one so that the heroes can do what they do best and stop him without too many complications. Loki being used by a bigger evil is also obviously meant to set up future films, but I felt like it could have done with being a bit more clearer. But again theres a flip side, as developing this background more may have distracted from Loki being a focal point and a credible villain, so there’s a fine balancing act that is being struck here. As a standout performance, I enjoyed the portrayal of Bruce Banner/The Hulk as a skittish scientist who everyone also has to be really careful around so he doesn’t transform and pulverise them.

Even though the story is quite simple, the film as a whole is certainly not lacking in ambition and scope. The final battle covers a significant portion of Manhattan, with a full-scale alien invasion tearing through skyscrapers and the streets of New York City. Superheroes in NYC again is hardly a novel phenomenon (which the film itself pokes fun at with a Stan Lee cameo), but perhaps that’s very much intentional: The Avengers is not attempting to differentiate itself from other superhero films by trying something new and different, but by outdoing every other film in the genre on its home turf; taking all these established tropes and concepts and executing them in such a way that no other film could compete. In short, it becomes the definitive superhero film. The level of destruction is unparalleled, the production makes it feel like a comic book film full of colour and dynamic shots and poses, and there’s some gloriously over-the-tops moments while also retaining plenty of humanity. The film does have some faults as I mentioned, and doesn’t push the envelope in terms of finding a new angle to develop or evolve the genre, but it is an ambitious project that pays off through balancing a colourful cast of characters with large-scale action and an interweaving of stories to create an entertaining tapestry that solidifies itself as the apex of the genre.

-

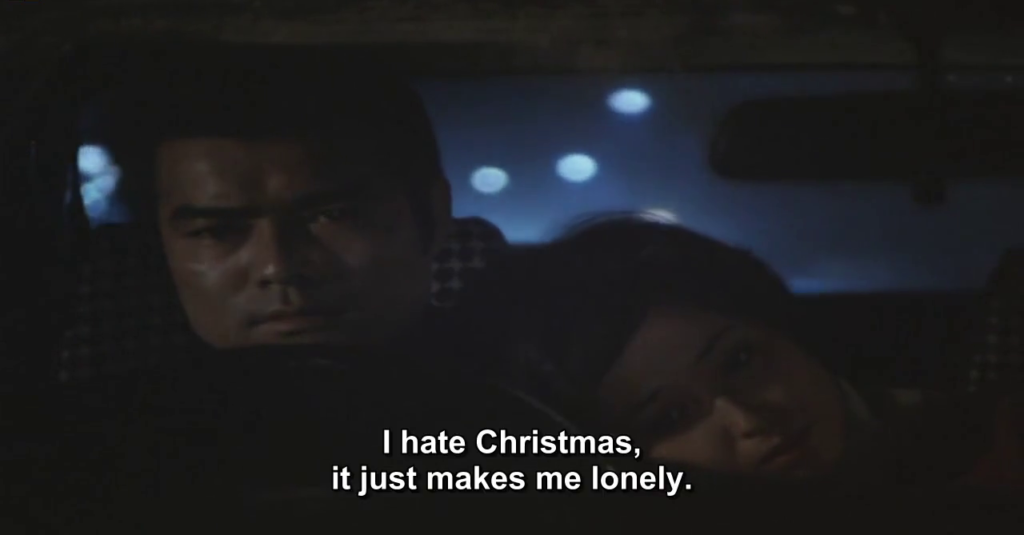

#278 – Blue Christmas (1978)

Blue Christmas (1978)

Film review #278

Director: Kihachi Okamoto

SYNOPSIS: Dr. Hyodo addresses a science conference saying that aliens are visiting Earth, which causes an uproar. Shortly after, Hyodo disappears, and reporter Minami is put in charge of investigating what has happened to him. Meanwhile, people across the globe who have seen aliens seem to have their blood colour change from red to blue. This leads to a distinction between those with red and blue blood, and the world governments doing whatever they can to suppress and get rid of those with the blue blood.

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: Blue Christmas (Also known as Blood Type: Blue or The Blue Stigma) is a 1978 Japanese science-fiction film. The film’s story essentially centres around the premise that people across the globe are seeing alien ships, and when they do, their blood inexplicably turns blue. As this phenomenon is happening across the world, the film features a large cast who are all responding to the crisis differently, although the film is primarily split into two halves, each focusing on a specific character. The first half mostly centres on Minami, a reporter who is given the task of investigating the disappearance of Dr. Hyodo, who had warned about the appearance of the aliens, only to be met with scorn from the scientific community. As Minami continues his investigation, he starts to uncover a link between the blue blood phenomena and Hyodo’s disappearance, as various powers are trying to supress the existence of such blue-blooded people as much as possible. The film’s plot is very dialogue-heavy, and there is a lot of switching between characters to give the impression of the scale of what is happening. It builds complexity and intrigue, which keeps the viewer engaged, but it doesn’t necessarily go anywhere: but that’s not really a bad thing, and in truth, that’s the point the film is trying to make…

As the film progresses, the governments of the world introduce increasingly robust measures against those who possess blue blood; covertly killing them off, and when their existence cannot be denied anymore, start to issue propaganda citing that there is no way of knowing what danger they may pose i the future, allowing them to present policies such as shipping them off to camps to the public with approval. As you may be able to work out, this film is a big metaphor for fascism, and the attempted removal of those who are different or impure so they do not “contaminate” everyone else. There is at one point a TV documentary about Hitler and WWII shown in a scene just in case the similarities weren’t apparent enough. It’s not a complex analogy of fascism that explores its roots, effects and any other issues, and for that I think it makes a surprisingly decent portrayal of it. By this, I mean the simple fact that the only distinction between the two people is the colour of their blood: nothing else…there is simply no threat or danger that can be discerned from this (in fact, those who have blue blood seem to have a much more calm disposition, and their anger and hatred have vanished since their alien encounter), and the fact that there is no rational foundation or basis for discrimination or fear is precisely a definition of fascism: that it creates an “other” that is deemed dangerous and a perceived threat so that people will gladfully accept any measure to get rid of them.

The first half of the film, told primarily through Miname’s investigation, looks at how fascism emerges from the separation of red and blue bloods, and how people respond to it. The second half of the film deals more with a human story of two people caught in the middle. Military soldier Oki starts a romantic relationship with Saeko Nishida, a hairdresser, only for Oki to find out that she has blue blood. He continues seeing her, but the government is fabricating an attempt by blue bloods to overthrow the government, which they will use to justify enforcing tougher measures against them. Oki is assigned to kill Saeko, which he does out of mercy for her, before turning his gun on the other soldiers, so they kill him. I don’t think there’s too much that stands out in this love story between two sides of a divide; it plays out as you would expect, and offers no real surprises. It’s done decently, but nothing remarkable. Another interesting fact is that we never actually see any of these aliens; only in one scene do we see still shots of vague alien ships. This again reinforces the heart of the film that it is not an outside force which divides people, but their own fears about wht is different. Overall, Blue Christmas is a decent film, which delves into the power of fascism with an understanding of its complexity and operations. The film is shot with skill, and the variety of locations gives the impression of a global problem which affects everyone. The story is not overly remarkable, and there’s nothing too memorable about it, but it is an interesting dive into the human condition and what causes rifts in society, and it is explored with a great amount of thought and care, which makes it an interesting watch, although there are plenty of films which explore this subject matter (especially in science-fiction) in a more structured way.

-

#33 – Blade Runner (1984)

Blade Runner (1982)

Film review #33

Director: Ridley Scott

Do androids dream of electric sheep…?

SYNOPSIS: Los Angeles in the year 2020; six Replicants, androids who were built to mimic humans almost perfectly, have managed to escape an off-world colony, and have landed on Earth, where they are illegal. Rick Deckard, a retired “Blade Runner” (a cop who hunts down replicants), is brought back to the force to hut down and “retire” these replicants. He visits Tyrell, the head of the corporation that built the replicants to examine a test that can distinguish a replicant from a human. There. he meets Rachael, an experimental replicant who believes she is human, implanted with false memories to this end. After 100 questions, the test is still inconclusive about whether she is human or not.

Meanwhile, two of the renegade replicants find an employer of Tyrell corporation, and interrogate him to find a way to meet Tyrell, trying to find away their four year lifespan that is built into them. He suggests they find J.F. Sebastian,the designer of the replicants. Later, Rachael visits Decker at his apartment, trying to prove her humanity by showing him a family photo, but he rejects it, saying it is just somebody else’s memories, causing her to leave in tears. Meanwhile, one of the replicants, Pris, has befriended Sebastian, and he takes her home, where he makes animated dolls using his skills as a designer.

At one of the replicant’s apartments, Deckard finds a photo of a replicant and a snake scale, which he eventually uses to track down a replicant called Zhora to a club. After chasing her through the streets, he catches her and “retires” her. Reporting back to the police, he is told that Rachael has gone missing, and he is to add her to the list of replicants to be retired. Deckard is then attacked by Leon, another replicant, but Rachael appears and shoots Leon, saving Deckard’s life. The two return to his apartment, where Deckard promises not to kill her.

Meanwhile, at Sebastian’s apartment, Roy, the leader of the renegade replicants turns up to tell Pris that they are the only two left. They persuade Sebastian to get them to meet with Tyrell, where they hope they can get him to extend their life. When Roy arrives however, Tyrell tells him that it is impossible, and Roy confesses that he has done many terrible things, but Tyrell dismisses this, saying how special he is in a rather messianic moment. Roy then kills Tyrell and leaves alone.

Back at Sebastian’s apartment, Deckard has entered, and after a brief fight with Pris, kills her just as Roy returns. The two engage in a lengthy fight and chase, ending on a rooftop, where just as Deckard is about to fell to his death, Roy unexpectedly saves him, and dies himself. Back at Deckard’s apartment, he finds Rachael and the two leave the apartment as the movie ends…

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: Blade Runner is primarily an action film, but it operates on a number of other levels too, utilising notions of the film-noir genre, and using a lot of different religious symbolism and references means this film can be quite complicated, and one could interpret the film in a number of ways.

The film has a very distinct aesthetic. Taking place in the not-so distant year of 2019 in Los Angeles, it is a very “retro-fitted” future, where the city has been developed by merely building over or around the current architecture and structure, so the city is a mass of crowded, narrow streets, and tall skyscrapers that block out the sky from the ground. It reminds me a little of the “Walled City” of Kowloon, in which the city was built on top of itself so much it had to be demolished. Also in the movie, we get glimpses of other future technology, including the hovercars, which are one of the most memorable images from the movie. The images of the Los Angeles skyline in this movie are probably the most famous images to come out of this movie.

Blade Runner has become quite a popular movie over the years, though it didn’t start that way. It was a box office failure (Barely breaking even), and the film was plagued by differences between director and studio, the most controversial part being the voiceover “diary entries” which the studio wanted, but Harrison Ford didn’t, the studio thinking the movie was too complicated without them. The director’s cut edition does not include them, and I think the movie is better without them. The film has quite a large “cult” following, not quite entering the mainstream cinema, but it is on the fringes as a very unique example of science-fiction storytelling, and a remake or sequel has often been discussed.

Very little in this movie is obvious, it is full of strange images and numerous sub-plots that intertwine. The image of Roy, the replicant leader having a very messianic persona, who is looking to save his fellow replicants from the curse of the four year lifespan is an interesting one. He is played very well, torn between these two concepts of being an advanced replicant and having genuine emotions, but not quite achieving them in human form. The human vs Replicant line is blurred further when the notion is brought up about half-way through the film that maybe one should question whether Deckard himself is a Replicant. Though this is never answered, like a number of elements in the movie that are left unresolved at the end, the viewer is invited to make up their own mind.

Overall, Blade Runner is an important movie in terms of science-fiction cinema. It invites the viewer to take it seriously through it’s multiple twists and turns, and interpret what it is happening for themselves. It’s dramatic “neo-noir” style makes it a tense and slick movie that presents the future in a unique way, and is a movie that has stood the test of time, making it an enjoyable and watchable movie.

-

#32 – Barbarella (1968)

Barbarella (1968)

Film review #32

Director: Roger Vadim

1960’s science-fiction based on the comic strip of the same name…

SYNOPSIS: Barbarella is contacted on her ship by the president of the Republic of Earth for a top secret mission. She is to retrieve Doctor Durand Durand from the planet Tau Ceti, where he was last seen. Durand has invented a positronic ray, and disappeared in an unknown sector of space. As Earth has been at peace for centuries, weapons are unheard of, and if the positronic ray falls into the wrong hands, it could spell disaster for Earth. As she is on course for the planet though, her ship malfunctions and she crashes on the surface of Tau Ceti…

Barbarella heads out onto the surface, and meets twin girls, who knocker her unconscious and drag her away. When she awakens, she is surrounded by a number of children, who have tied her up and use dolls with razor sharp teeth to bite her. Fortunately, Barbarella is rescued by A huntsman, Mark Hand, who is on the lookout for errant children. She offers to reward him, and he suggests they make love. She is surprised he wants to do it physically, as people of Earth now use pills and psychological analysis instead. She however agrees, and departs from Tau Ceti in her ship, agreeing that sometimes the old ways are the best…

Her ship crashes through the surface of the planet into a labyrinth, badly damaging her ship. She exits her ship and is knocked out by a rock slide, but is rescued by an angel named Pygar. He explains that the labyrinth is where all the people who are cast out of Sogo, the city of night, are forced to live. She is then introduced to Professor Ping, who offers to repair her ship, and suggests she heads for Sogo if she is looking for Durand. Pygar, using his wings gives Barbarella a lift to Sogo. Battling the Great Tyrants black guards along the way, they finally arrive. The two are briefly separated when Barbarella is assaulted by two of the residents. She is saved however, by a one-eyed woman, and Barbarella heads off to search for Pygar.

She finds him and the two try to escape, but find themselves trapped in a strange chamber with an odd liquid beneath the floor. The Concierge, who serves the Great Tyrant who rules Sogo, steps in and takes them away, explaining that the liquid is Mathmos, a demon of sorts that feeds on the negative energy of the people of the city. The two meet the Great Tyrant, who is none other than the woman who rescued Barbarella earlier. Pygar is left to be “crucified” by the Tyrant, and Barbarella is sent to be pecked to death by birds. She is rescued by Dildano, the leader of the resistance, who want to overthrow the tyrant. She offers to thank him by making love, but this time he wants to experience the use of the pill like on Earth. The clumsy Dildano explains that the only time the tyrant is vulnerable is when she is asleep in the Chamber of Dreams, and hands her the invisible key to her lair and sends her on her way.

Barbarella is soon captured by the Concierge again, who traps her in a “pleasure machine”, which will cause her to die by overexposure to pleasure. Barbarella however, being too full of good and pure energy, breaks the machine, and finds out that the Concierge is none other than Durand, who looks a lot older than she was told because of the effects of the Mathmos. He traps Barbarella in the Chamber of Dreams with the Tyrant, so he can proclaim himself ruler of Sogo. His plan is interrupted by Dildano, whose revolutionary forces start to attack, he decides to take them out using his positronic ray. The Tyrant however, releases the Mathmos to destroy Durand and Sogo. She and Barbarella manage to escape by being protected in a focefield apparently generated by Barbarella’s goodness. The two find Pygar and they all fly back towards Barbarella’s ship together.

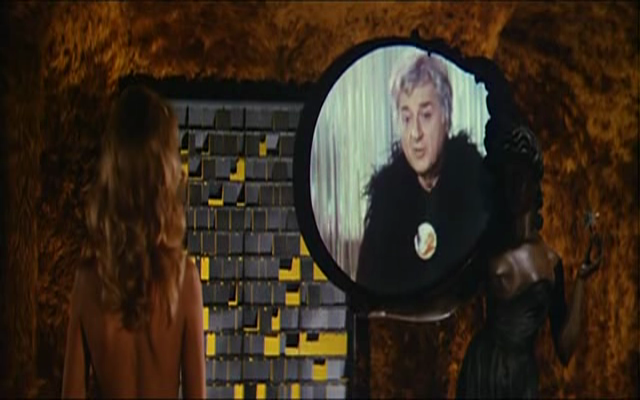

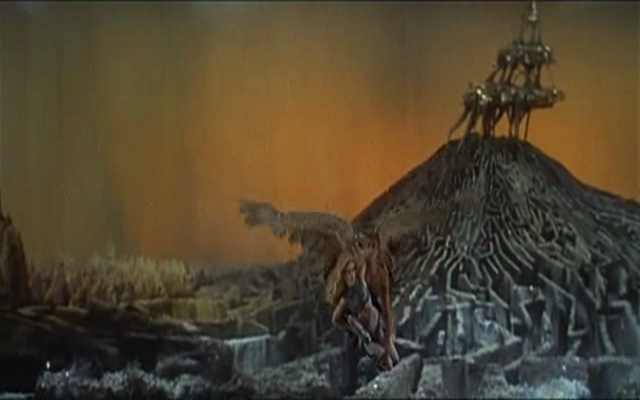

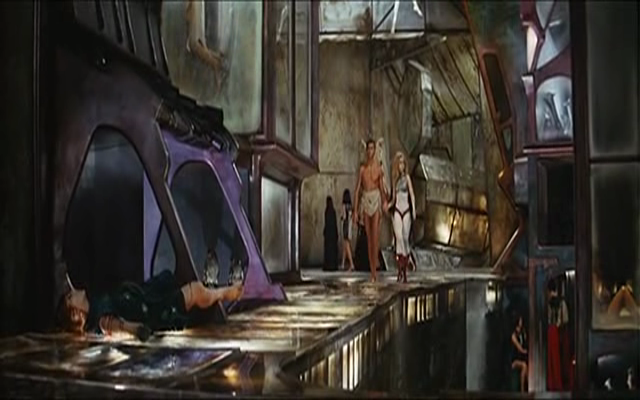

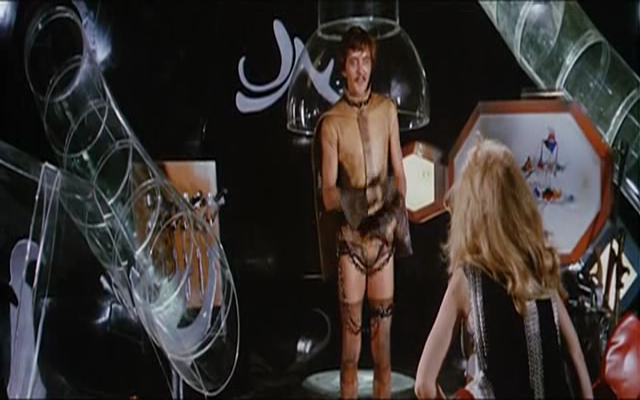

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: This is an odd sort of film. It seems to be somewhat of a parody of science-fiction, with everything being very tongue-in-cheek. It is a very 60’s film; the psychedelic images of the Mathmos throughout the movie, the scene with the not-so-subtle smoking scene of some sort of drug, the use of “love” in direct reference to how “Peace” was used at the time, and also the soundtrack, which sounds very much like a soundtrack you would find in a more “reality-based” movie of the sixties, or in one of the clubs of the time, quite a difference from the spacey soundtracks one is used to…

Perhaps what makes this movie stand out is the use of a female lead role; something you very rarely see in science-fiction, and almost completely unheard of back then. The erotic and suggestive undertones of the movie really need the use of that innocent, good-natured Barbarella though, and had this been a more serious or traditional science-fiction movie, I’m guessing this would have never have even been given approval to be made. There’s plenty of phallic imagery throughout the film too, so you’re never really taking this film too seriously, as it always one step away from being a complete parody of what itself.

Barbarella was a box office and critical failure, not being released in English until nine years after it was released in France and Italy (The film was filmed in France, and the film was filmed in both languages.). Despite this though, I think it is one of the more memorable science-fiction films of that era, as it does something that is very different. It does not really try to overcome the cheap design and props either, it in fact seems to revel in it. To testify to this, it has a small cult following, and a remake has been talked about it on and off for years. I imagine it would be quite difficult to capture the essence of the original movie, as the decade it was produced in provided a very strong context in which this movie could thrive.

Overall, Barbarella isn’t your typical science-fiction from that era, it is something a little different that never takes itself too seriously. It is important to consider the era it was made, as it plays off many of the definitive aspects of the sixties to appeal to that audience. It’s a little “off the radar” in terms of mainstream science-fiction, but this is why it becomes quite a good parody of the more commercial ones, and having a woman in the lead role in this context is quite subversive and risky, really rounding off this very unique film.

-

#31 – The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension! (1984)

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension! (1984)

Film review #31

Director: W.D. Richter

Cult sci-fi about a modern renaissance man and his skilled team…SYNOPSIS: Out in the desert, a group of people have gathered for a test of a new jet car that could break through into the 8th dimension, however, the driver has not yet arrived. So while the final checks are being made, one of them goes to make a call…

In a hospital operating theatre, Dr. Buckaroo Banzai is operating on a patient. Using his skills as a brilliant doctor, he saves the patient, and is impressed by his assistant, and asks him if he would like to join his team. Banzai is then shown to arrive by helicopter at the test site for the jet car. The test starts and Banzai is driving the car as it breaks the sound barrier and continues. Banzai continues despite being order to abort, and he heads directly towards a mountain. Just before he crashes, he disappears into a strange void full of strange shapes and landscapes, as soon as he enters this strange dimension though, he exits out of the other side of the mountain, and so completing a successful attempt to travel into the 8th dimension. Attached to his car though, is a strange creature…

Meanwhile, Dr. Emilio Rizardo, committed in an asylum for the criminally insane is watching the report about Banzai’s achievement on TV. Banzai’s mentor, Dr. Hikita talks about the device that made it possible: The oscillation overthruster. A flashback shows how both Rizardo and Hikita managed to open a portal into the 8th dimension many years ago, and how Rizardo briefly entered the dimension and apparently went insane. Having now built his own oscillator overthruster to reenter the 8th dimension, he phones up a “John Bigbooté”, and escapes the asylum to meet up with some friends at Yoyodyne…

Back with Banzai, he and his team and band, the Hong Kong Cavaliers are doing a gig in New Jersey. Looking out into the crowd, Banzai sees a woman crying. He asks her name, and she responds as Penny Priddy. She is down on her luck, and Banzai, being the renaissance man he is, plays her a song on the piano (Mistakenly calling her Peggy). However, this fails to lift her mood, and is about to shoot herself in the head until someone knocks her and the bullet flies into the air, and she is taken away by police. The team reflect on how she looks exactly the same as his ex-wife. They then learn that Rizardo has escaped, and they have also detected a cloud-like mass over southern New England. Banzai goes to meet New Jersey, the doctor Banzai was working with in the operating theater, and introduces him to the team. Banzai and Perfect Tommy find Penny in jail and bail her to join Banzai.

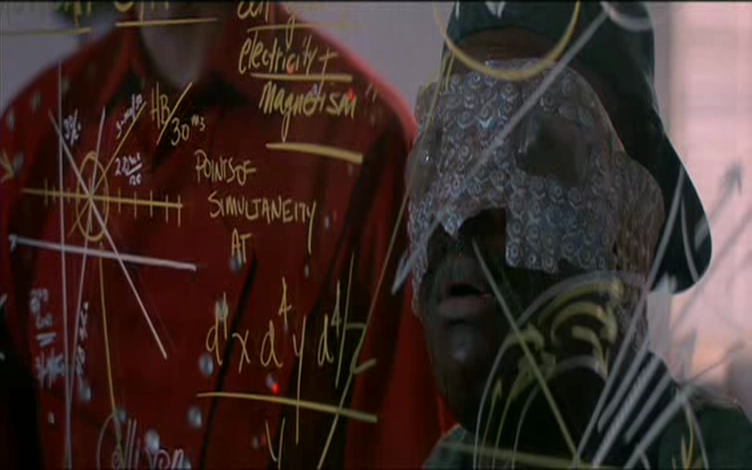

At a press conference, Banzai explains his achievement in breaking through the 8th dimension, and how his parents died on the hunch that these extra dimensions house aliens and new races, and they reveal the creature they found attached to Banzai’s car. Meanwhile, an alien spaceship high in orbit above the Earth is watching, and launches a thermopod. Banzai gets a call from the president, and recieves a shock from the line, after which, he is able to see through the disguise of Lectroids, the aliens from the 8th dimension, who are trying to take over the world. They kidnap Hikita, and Banzai and the Hong Kong Cavaliers give chase.

The thermopod the aliens launched lands in some woods, and the Lectroids pick up the signal and give chase. Some hunters and cops get there first, and while one of the aliens who emerges is shot, the other escapes. Banzai radios Rawhide, one of the Hong Kong Cavaliers to return to their compound and dig up any information on Yoyodyne industries. The Lectroids find the thermopod and eliminate all the witnesses, but Banzai is close behind. The Cavaliers send out a message to the Blue Blaze Irregulars, a network of volunteers who help out Banzai when he needs it. Two of them in the area, Casper and Scooter Lindley, receive the call and head to Banzai’s aid. He rescues Hikita from the back of the van, and explains he can see the Lectroids, and he knows that they are from planet 10, by way of the 8th dimension. Banzai is rescued by Casper and Scooter, while Hikita escapes on a motorbike.

At the compound, the team are investigating Yoyodyne, and they find that all the employees have the first name “John”, and appeared at the same time that The War of the Worlds broadcast by Orson Welles that announced an alien invasion in 1938 wasn’t a hoax, but was real, and the Lectroids came to Earth on that day. Meanwhile the alien from the thermopod arrives and says he needs to see Buckaroo. calling himself John Parker, he delivers a holographic message from The Black Lectroids, a species of peaceful aliens who banished the Red Lectroids to the 8th dimension. Their leader, John Whorfin (All of the Lectroids have the first name John), now resides in Dr. Rizardo, and will try to steal the overthruster to return to the planet 10 to take revenge. Sure enough, an attack on the compound follows, and Penny is kidnapped, along with the overthruster. The Black Lectroids warn Banzai to retrieve the overthruster, or they will stage a nuclear strike against the Russians and start World War III in order to protect themselves. Rizardo contacts Banzai, telling him to come alone to Yoyodyne industries with the overthruster…

Banzai heads in in his jet car, ordering the Hong Kong Cavaliers to come in after 30 minutes to “mop up”. Banzai is captured by Rizardo/Whorfin and ordered to tell the secret of the overthruster, while the Cavaliers, backed up by the Secretary of defense move in. Banzai manages to escape and rescue Penny, then Banzai and John Parker head off to find the ship the Red Lectroids have been constructed. When Whorfin, and Bigbooté take off in it, Banzai and Parker give chase in a spare thermopod, and blow up Whorfin’s ship with him in it. The victorious Banzai then returns, into the arms of Penny…

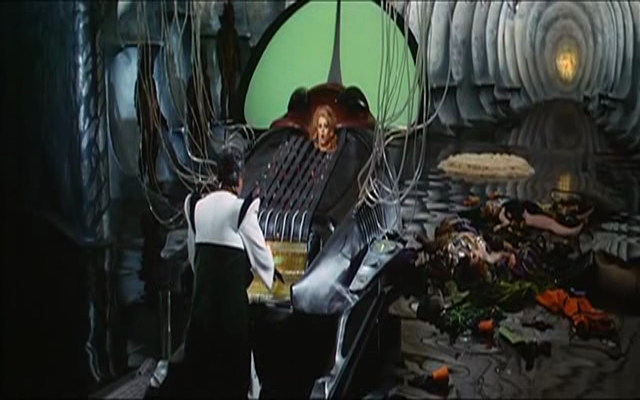

THOUGHTS AND ANALYSIS: This is an odd film. It is (I think) primarily a science-fiction, mixing elements of satire, romance and comedy. It has a distinctive 80’s flair that is of its time; the soundtrack, the outrageous costumes and the humour all add up to create that eighties vibe. The special effects in Buckaroo Banzai were really good too; the costumes of the Lectroids are very well done, and though most of the sets aren’t very elaborate in terms of science-fiction, they are still well put together. The jet car and the alien ships have sort of messy aesthetic to them, unlike the more sterile sets one might usually see in science-fiction.

There are a lot of interesting ideas in this movie. The world created in this movie seems very rich and interesting, introducing a rage of interesting characters in Buckaroo Banzai and his Hong Kong Cavaliers. However, I think that the film just isn’t long enough to realise all these interesting ideas in just 102 minutes. This is no more prevalent than in the protagonist of the film: Buckaroo Banzai, a regular renaissance man; who is a surgeon, rocket car driver, rock star and physicist. The film spreads out Banzai across all these areas, in which he handles all with ease. The characters of the Hong Kong Cavaliers, such as Rawhide and Perfect Tommy seem to be really interesting characters, but are never fleshed out during the film. As I said, a rich world has been created, but it is never really elaborated upon. I suppose one should just enjoy the ride that the film offers, rather than trying to overthink what is happening in what is mainly a comedy film. A sequel was planned, which was mentioned at the end of the film, but it was sadly never realised.

With regards to the reception of the film, it failed at the box office, making only half it’s budget back. Its failure in this respect could be due to a number of reasons. As I mentioned earlier, the movie creates an interesting backstory, but there just isn’t enough time to elaborate on it, making the movie a little confusing. The deadpan humour of Buckaroo Banzai also may not be to everyone’s tastes too, I imagine if you went in to see a comedy film as this was advertised, you might not “get” the humour on offer. It’s lack of success can also be attributed to the fact that it was never really advertised to a mainstream audience, instead promotions and advertisements were done at various science-fiction conventions, appealing to that core audience which it would enjoy it, rather than the public in general. Despite it’s shortcomings in the cinema, it has become a cult movie, gaining a small but dedicated fanbase, and a number of spinoffs in the form of novels and comics have been released since the movie, which shows the movie still has that appeal to a circle of people. I think the film can capture one’s imagination quite well with the possibilities of this renaissance man and his band of merry men.

In short, I think Buckaroo Banzai is a fun film; the characters are interesting, the production is slick, and the special effects are well done. It is pretty much a science-fiction film for science-fiction fans though, and other people may not enjoy the humour or the story that the film has to offer. Appealing to the science-fiction core seems like a double-edged sword really: They will get the humour, the characters, and perhaps the confusing plot, but science-fiction is a genre that hinges on it’s audience paying special attention to the details, and since this movie skips over some of the finer details, it can seem a little confusing, even to the core sci-fi fan. But again perhaps this leaves a lot of space for an imaginative mind to fill in the gaps and have lots of fun with the world that is established in the movie. Regardless, it is a fun movie, and if sci-fi is your thing, this should be your thing too.

And remember: “No matter where you go…There you are.”

-

#30 – Alphaville (1965)

Alphaville (1965)

Film review #30

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Welcome to Alphaville, where human emotion is outlawed, and logic is all powerful…

Lemmy Caution, a secret agent from the “Outlands” arrives in Alphaville, a city on another planet, which is ruled by the all-powerful machine Alpha 60, who has outlawed all emotion. Posing as Ivan Johnson, a journalist working for the Figaro-Pravda, he has a number of missions to accomplish: First, he is to find missing agent Henry Dickson, next he must capture or kill Professor Von Braun, the creator of Alphaville, and finally is must destroy Alpha 60 itself. Caution checks into his hotel, acting hostile to those around him, but no one ever shows any response to his actions. Caution enters his room, and checks around and casually kills an agent hiding in his room. He then meets Natacha Von Braun, the daughter of Professor Von Braun, whom he asks to arrange a meeting with the Professor.

Caution heads to the Red Star hotel, where he has tracked down missing agent Henry Dickson. He tells Caution that those who do not assimilate into the state are pushed to suicide, and Dickson soon dies. Caution then returns to ask Natacha for help in meeting Professor Von Braun, but she insists she has never met him, despite being her daughter. Caution begins to fall for Natacha, but as she was raised in Alphaville, she does not understand words such as “love” or “conscience”, and has trouble feeling any sort of emotions. Caution is taken to a swimming pool, where a public execution is taking place. He is told that fifty men are executed to every one woman, and the executions are taking place next to a group of women synchronised swimming. When Caution tries to get close to Professor Von Braun, he is arrested and thrown into an interrogation room.

Caution is then questioned by Alpha 60, who tries to ascertain his purpose in being in Alphaville. Caution is reluctant to co-operate with a machine, but Alpha 60 suggests that he becomes a spy for Alphaville, and is released in the meantime. Caution heads back to his hotel room, where Natacha is waiting for him. He talks to her about things such as poetry, but she does not understand, and reaches for the “bible”, which every room has. Caution is surprised to find that this is not a bible at all, but a dictionary, and Natacha explains that the bible needs to be changed regularly, as Alpha 60 is constantly removing words which are no longer necessary. Caution makes her realise that she was not born in Alphaville, but was brought there from New York when she was a child, and so she still has the capacity to feel these emotions.

Caution finally heads for one last confrontation with Alpha 60 and Professor Von Braun. He finds the Professor, and he offers very little resistance, he tries to tempt Caution with joining Alphaville, or ruling a galaxy, but when he finally refuses Caution’s final attempt to persuade him to rejoin “the outlands” (The world outside of Alphaville) Caution finally shoots and kills him.

Turning his attention to Alpha 60, Caution poses a riddle to the supercomputer, and since it has no understanding of poetry and such, it manages to defeat itself and shut down. Caution finally gets in his car with Natacha and drives off down the highway out of Alphaville. Natacha finally realises that her individuality and understanding of her own feelings can save her, which deals the death blow to Alpha 60. As the two drive off down the highway, Natacha is able to say the three words that set her free: Je vous aime (“I love you”)…

Jean-Luc Godard, the director of Alphaville, was one of French cinema’s most innovative directors during the 1960’s, where he criticised films for their lack of innovation and experimentation. Alphaville takes the distinct genres of science-fiction and film noir and combines them to create a film that is a strange mix between the two. Lemmy Caution, a character that had appeared in a number of previous films set in the present, is here thrust into a more dystopic future, and there is a contrast with this weathered old detective going up against a futuristic supercomputer who controls a planet. This future however, is not like the future we see in most other science-fiction films, it is instead very similar in terms of design to the present. The film was shot entirely in Paris, using different areas of the city for different scenes such as the electric company for the headquarters for the supercomputer Alpha 60, for example. This perhaps makes it not so much a futuristic setting, but more of an alternative present, as the film references that it is taking place in the twentieth century.

There are no special effects or flashy props used in Alphaville; Everything you see on screen is shot directly on location in Paris. Even the more modern (or futuristic) architecture is from buildings which were recently built in the city, and which would be seen as quite futuristic in comparison to the older architecture of the city. The science-fiction aspect of this movie is not so much concerned with the landscape and the technology, but rather about how the people are affected and governed by a machine. The “bible” is an interesting concept that crops up during the film. It is mentioned at the beginning that every room should have a bible, and near the end we find out that this bible is actually a dictionary, which is composed of all the words that Alpha 60 has deemed acceptable, and it is referenced that constant revisions are made when Alpha 60 deems a word no longer necessary. This concept is quite similar to the idea of “Newspeak” in 1984 By George Orwell, in which the ruling party decides which words are necessary, and which ones should be erased from history, altering past documents to suit the present’s needs. The future in Alphaville is always undergoing constant revision as the supercomputer at the head of it all processes new information…

The film is quite experimental in nature. In keeping with Godard’s mantra of innovation and experimentation, the narrative is composed of Caution’s journey through Alphaville, and the intermittent voice of Alpha 60, who serves as a narrator of sorts at certain parts of the movie. During these narration scenes, we usually see flashing images of equations, words and images that are cleverly inserted to accompany the powerful and absolute statements that the computer dictates.

Alphaville is a mix of science-fiction and film-noir, combining two genres which traditionally don’t go together. It has a sense of mystery and drama in a world which is full of mysteries itself. The concept of computer’s ruling humans and outlawing emotions is hardly new (Or maybe it was when it was released?), but it is a fresh take on the subject, by taking the ordinary and everyday, and gives it a “what-if?” twist into the future. It also cleverly references some of the other works of literature and film from that time, using them to rebel against the objectivist mind of the computer. Overall, I would say it is definitely worth a watch.

-

#28 – Destination Moon (1950)

Destination Moon (1950)

Film review #28

Directors: Irving Pichel, Walter Lantz

The first science-fiction movie to be produced post WWII about a trip to the moon…

As the latest test launch of a V-2 rocket fails at a top secret launch site in America, government funding is pulled and rocket scientist Dr. Charles Cargraves, and General Thayer have to rethink their plans. They hire Jim Barnes to aid them in creating a rocket that can take them to the moon. They persuade a group of corporate American investors and captains of industry to fund the project. At first skeptical, Cargraves convinces them that they are not the only ones who want to get the moon, and that whoever can put missiles on the moon first will control the Earth…

Two years pass and the rocket is just about ready for takeoff. Fear has been building in the media that the rocket may cause a number of consequences to the public, including radiation, so Cargraves steps up the launch schedule to avoid giving the government time to stop them, since “There are no laws against launching a space rocket yet.” Cargraves, Thayer and Barnes are joined by Joe Sweeney, who handles the radio and communications equipment in the shuttle. He does not believe that the rocketship will work, and only agrees to join in just to prove this. While they are making final preparations, a government official tries to gain access to the launch site with a court order, banning the rocket from launching. Cargraves hears of this and quickly rallies his crew into the rocket and to take off before the official can reach them, feigning ignorance of why he is there.

As the rocket takes off, the crew experience the G-force from launching, and start to experience weightlessness. They take a pill to counteract the feeling of “spacesickness”, and take a look out of the window to see the Earth moving away in the distance, as Sweeney still can’t believe the rocketship worked, telling the others he wants to head back because the moon is just “something to look at”. While travelling through space, they find that one of the antennas has frozen, and they have to take a walk outside the shuttle to go and fix it. They very nearly lose a crewmember as he drifts off into space, but another crewmember uses an oxygen tank as a propulsion device to go and rescue him, and the four continue on their voyage to the moon.

Upon making a successful landing, the crew head out onto the surface, and Cargraves claims the moon “In the name of all mankind”. They then receive a transmission from Earth, and are interviewed for a broadcast to be sent all over the world. The team then splits up to research the different aspects of the moon. Cargreaves photographs Sweeney seemingly holding up with Earth, like a “Modern day Atlas”, and Thayer takes some mineralogical surveys, finding a large uranium deposit on the moon.

Back at the ship, Barnes is calculating the take off with Earth, and comes to a troubling conclusion: The rocketship is too heavy to take off and make it back to earth. He goes outside to report this to the other crewmembers, and they spend the next 24 hours stripping the ship to make it lighter. In the end, they are still 110 pounds too heavy, and they decide they have to leave someone behind, and decide to draw lots between Thayer, Cargraves and Barnes. Sweeney goes outside while they argue and decides to sacrifice himself. Cargraves then comes up with a plan to take out the radio and to close the airlock without someone having to do it manually, so they can throw out the last spacesuit, leaving the rocket light enough to take off from the moon and towards Earth. The film finishes with the phrase on screen: “This is the end…of the beginning”.

Destination Moon was the first movie to be put into production post WWII about space travel. It was not the first released however, as when it was delayed, Rocketship X-M was quickly produced and made in under three weeks to beat Destination Moon to release and ride the hype it had created (As I discussed in my Rocketship X-M review). Destination Moon is a slick and carefully considered movie about the prospects of space travel, and the movie tends to being as accurate as possible in terms of technology and science. For this reason, there are no robots, aliens, monsters or UFOs which dominated science-fiction at this time in the movie, but it is billed as a semi-documentary with regards to it’s execution. The plot and feels almost secondary to the science.

When this movie was released, the general public had very little idea what space travel would be like (The first man-made objects hadn’t even reached space yet), and the movie does it’s best to be informative and speculative at the same time. This is accomplished in a number of ways, firstly when Cargraves is trying to get the captains of industry to invest in the rocket, he shows them a Woody Woodpecker cartoon, which explains the whole concept of how the rocket works in this colourful and simple way not just to the investors, but to the audience too. Also the character of Joe Sweeney, played by a comedian acts as the “everyman” aboard the crew, with the rest being scientists or experts in their field. He is perhaps the most relateable character, with his distinct Brooklyn accent and his lack of knowledge about space travel, the other crewmembers have to explain to him what is happening throughout the journey, and the audience learns what is happening along with him. The speculative nature of the film reminds me very much of Contact, which itself is about the “What-ifs?” about first contact with extraterrestrial intelligence.

When this movie was released, it was billed as a high budget production. Just the fact that it was released in colour in 1950, when very few films were, is a testament to this. Though expensive and accurate in it’s time, nowadays it looks very much out of date. The moon set is a large 13ft matte-painted landscape, with holes cut out and light shined through them to create stars. This was an often practiced technique at the time, but nowadays looks rather crude. Since we have now put man on the moon unlike when this film was made, we can see that the film comes somewhat close to capturing the bleakness of the lunar landscape, but not close enough when compared to actual photographs taken from the moon, and our suspension of disbelief when looking back at this film cannot be maintained.

Overall, I would say that Destination Moon was a pretty important film for it’s time. It attempted to accurately speculate what a trip to the moon would be like, without there being any successful attempt to get into space at the time. We can look back on it now and pick apart the discrepancies between this and actual space travel. It shows that space travel is both a fantastic adventure and a perilous one, supported by a story that has comedy, drama and speculation altogether makes it is a bit of cinematic history. It is a little bit of a departure from the “disaster” sci-fi movies of that era, where there was always a monster or alien race looking to wipe out the Earth, and it is perhaps a refreshing change: One of hope and prospect rather than the terror associated with scientific and technological advances as portrayed in other films of the same era. This departure makes it stand out from the others, and if you want to watch a movie from that era, it is worth your consideration, you might even learn a little something about space travel too.

-

#27 – The Core (2003)

The Core (2003)

Film review #27

Director: Jon Amiel

A sci-fi disaster film giving the B-movie sci-fi movie plots of yesteryear a big Hollywood makeover…

A number of strange incidents are occurring all over the planet, including people’s pacemakers stopping, pigeons falling out of the sky, and calculation errors aboard a U.S. space shuttle. Dr. Josh Keyes, along with his friend Serge Leveque do some investigating and find that the only explanation is that the Earth’s core has ceased it’s rotation, causing the magnetic field of the planet to disappear. Alarmed at what they find, they approach a top government scientist, Conrad Zimsky to confirm their findings. He unfortunately has to agree with the results. At a government meeting, the three explain to the politicians that if something is not done to restart the core’s rotation, the planet will succumb to a series of disasters and become completely irradiated without the Earth’s magnetic field to protect it from cosmic rays. Their plan: To plant a series of nuclear charges in the core to restart the core’s rotation, but in order to do that, they will need to travel to the centre of the Earth, which seems impossible. However, Zimsky has an idea…

Keyes, Leveque and Zimsky travel to the salt plains to Utah to meet a scientist named Ed Brazzelton (nicknamed “Braz”) who shows them his plans for a ship that could travel to the core, and an ultrasonic laser which could drill it’s way there. The ship would survive by being constructed with an element he has jokingly named “unobtanium”. He is reluctant to work with Zimsky, who took credit for his research some twenty years ago, but is swayed to construct this ship for them when they offer him the fifteen billion dollars needed to build it. Joining them is Rebecca “Beck” Childs, the pilot that helped save the Endeavour shuttle from crashing into L.A. earlier in the film, and her mentor and commander Robert Iverson to round off the crew, and the six of them train to complete their mission to save the planet, helped by Theodore Donald “Rat” Finch, a hacker who suppresses information on the internet to avoid mass panic and keeping the public from finding out what is happening to the planet.

When the ship is finally completed, the team have no time to lose and prepare to set off. Braz has named it Virgil, after the poet that guided Dante through Hell and to the centre of the Earth in the epic poem The Divine Comedy. As they travel through the Earth’s mantle, they enter a geode and get stuck on a crystal like structure. Braz, Keyes and Iverson exit the ship to cut the crystal away from the ship, but it is a race against time as the geode is starting to fill with magma from the hole the ship made. The crystal is cut, but a piece of falling crystal pierces Iverson’s helmet, killing him instantly. The ship sets off again, but is soon hit by a huge diamond, damaging one of the compartments. Leveque sacrifices himself to get the nuclear launch codes out the compartment of the ship that is jettisoned and crushed. Keyes screams to Beck to open the bulkhead and let him rescue Leveque, but Zimsky warns her not to, and she listens, much to Keyes’ anger at feeling he could have saved his friend.

When they head into the outer core, they find a severe flaw in their original plan, the density of the core means that they don’t have enough firepower to restart the core. Zimsky radios to the surface to activate DESTINI, a secret project that could propogate earthquakes through the Earth’s core. Keyes refuses to abort their mission, meaning that when DESTINI fires, it will destroy Virgil. Zimsky snaps at Keyes saying he has no plan and he is going to kill them all. While Braz and Keyes are trying to figure out a plan unsuccessfully, Zimsky interrupts and comes up with one of his own: To eject each of the nuclear bombs in a seperate section of the ship at seperate times to create a cumulative ripple that will have enough power to start rotation. Keyes contacts Finch to hack into project DESTINI and delay it to allow time for them to complete their mission. Braz remarks that someone needs to deactivate a safety switch to jettison compartments manually, and whoever went would die because of the extreme heat in the tunnel. Braz himself volunteers and dies shortly afterwards.

As they are jettisoning the compartments, Zimsky and Keyes realise that the final bomb does not have enough power to accomplish their mission. Zimsky then becomes trapped in a compartment, and tells Keyes to use the plutonium that’s powering the ship to create enough power in the final bomb before the bulkhead shuts and Zimsky is jettisoned with the ejected compartment. The ship is now trapped without power, but Keyes has a plan to rig the unobtainium up like a solar panel to power the ship through the planet, the explosions successfully start the core rotating, and they arrive out of the core at the bottom of the ocean. They think they are lost their without power, until Finch finds them by tracking the whales circling the vessel. Keyes remarks that no one will ever know how close the planet came to destruction, and of the sacrifices of Iverson, Leveque, Braz, and Zimsky. That is, unless someone manages to leak that information. One week later, we see Finch sit down in an internet café, and uploads the details of what has happened onto the internet, and revealing the noble sacrifices of the heroes that saved Earth…

The Core is very much a big budget Hollywood take on the plots and concepts of old B-movies such as The Day The Earth Stood Still or War of the Worlds, in which a disaster is affecting the entire planet. The big difference between The Core and it’s predecessors has to be the use of special effects: Being able to convincingly create the image of a ship tunnelling through the Earth, or a freak thunderstorm wiping out Rome and the colosseum really drives home that sense of disaster. These special effects weren’t really cutting-edge for their time, but compared to the B-movies of yesteryear, they are amazing, and one might wonder what those old movies would look like with a Hollywood makeover (Then you should remember some of the recent Hollywood remakes that were terrible, and should forget all about that idea…). Despite the scale the disaster is shown on though, I found the movie to be a fairly easygoing affair, and quite an enjoyable journey. When I first saw that the movie was two hours long I figured I was going to either have to wait a while for it to get going, or I’d get bored half way through, but that never happened. The movie starts off strong and eases you in to a comfortable pace with some well defined characters with enough personality that makes those two hours really enjoyable. Not stand out amazing, but enjoyable.

This movie wasn’t so successful in the U.S. when it was launched, and only turned a profit when it was released worldwide. The main reason this movie is remembered is because of it’s numerous scientific inaccuracies, and is often slammed by scientists (In a poll which asked scientists about the worst science-fiction films, The Core was voted the worst). There are a lot of liberties taken with science in this movie, so it’s difficult to pick just one out. I suppose the worst offender would be that the loss of the core’s rotation would not have the effect it has in the movie: Pigeons would not start falling out of the sky, pacemakers would not just shut down, and “superstorms” would not occur and wipe out entire cities. If the core did stop rotating, the immense energy from the rotation would instead dissipate outwards into the mantle and evaporate the oceans, which would be a much more serious issue. The energy needed to theoretically restart the core (Which isn’t possible, since it just wouldn’t stop) would be equivalent to 500 times the amount of nuclear weapons in the world, rather than the 5 they use in the film. The worst effect of the core ceasing rotation in the movie is the loss of protection from “cosmic rays” that the magnetic field gives. While this is partly true (depending on what type of “cosmic rays” one refers to), the movie refers to “microwaves” being the main problem, but in fact microwaves aren’t affected by magnetic fields, and the sun does not put out enough energy in microwave form to make much difference anyway.

If you know nothing about any of these concepts, you can perhaps just accept them and enjoy the film, and indeed, the film is still enjoyable despite the errors. The trouble with this (and other movies like this), is when you centre a plot around science, the audience is encouraged to think scientifically, and when one does that, everything becomes undone and the science doesn’t add up. In the film’s defence however, it does tend to not take itself too seriously, what with naming an element “unobtainium” for starters, and citing it’s cinematic predecessors, we can take the inaccuracies in jest, and enjoy the ride.

Overall, The Core is a fun ride, and an easygoing film that takes advantage of a large budget, stylish design and production values. While not a massive hit compared to similar movies such as Armageddon, it still holds it’s own. However, the sheer inaccurate portrayal of scientific knowledge throughout the two hours means you shouldn’t show this as an educational film to a class of high school children for it’s scientific value. Put that aside though, and you have a perfectly watchable film.

-

#26 – Doomsday Machine (1972)

Doomsday Machine (1972)

Film review #26

Director: Herbert J. Leder

A disaster film in more ways than one…

A pair of American spies infiltrate a secret Chinese research facility and discover a doomsday machine, which will be activated in 72 hours. They take photographs and report back to the American government.

Meanwhile back in America, the spaceship Astra is being prepared to launch on a two year trip to Venus. Their launch window has been stepped up, and three of the men of the crew have been replaced by three women, incuding one woman, at the last minute, which has baffled the crew. Soon after the launch of the ship, military alerts are placed in effect across the entire world. It then dawns upon the four men and the three women of the Astra that they have been put together to restart the human race on Venus should the Chinese “doomsday machine” be activated. Sure enough, they look upon the Earth as it destroyed through a myriad of nuclear strikes…

As the seven-person crew continue to Venus, they realise that the weight of the ship means that a safe landing on Venus is impossible, and that the crew must be reduced to three to make a successful landing. They entrust the machine to make the decision for them, much to the chagrin of one of the crew. Two of the crew are involved in an altercation, and accidentally open the airlock, killing them both. Furthermore, another two leave the ship to dislodge a faulty booster to ensure the ships landing.

The two crewmembers are drifting off into space when they come across an abandoned soviet shuttle from an earlier mission, and go to board. They find miraculously that the craft is still operable and attempt to communicate with the Astra. There transmission is cut out and they are unable to hail them. Then, a voice calling itself the “collective conscious of the population of Venus” tells the craft that the Astra is no more, and that humans cannot land on Venus, because they have proven to be dangerous and destructive species with the destruction of their home planet. The voice then talks ambiguously about their being life beyond the universe as the film suddenly ends…

This film seems to have been plagued by a number of problems during it’s production. Primarily being that the film ran out of money before it being completed. The film was made in 1967, but an ending wasn’t made until 1972, when the rights were bought and the film finally released. The original budget itself wasn’t much to begin with, leaving the film to be classified very much as a B-movie. That said, movies have been made of higher quality with less money than Doomsday Machine had ($700,000 to be exact). There are very few sets or special effects, and there was a lot of stock footage used in place of actually making anything original, so I do wonder where all the money went…

The movie itself is a very bleak and unhopeful one. The Earth is destroyed, and the last seven members of humanity are picked off as a consequence of their own selfish actions, or circumstances which they cannot control. The ending does very little to leave a feel-good message in the mind of the viewer either. It is a depressing “what-fi” secenario that is played out before us, and sugar coating it with a happy ending may have taken away that dire warning. Being released during the Cold War, it’s message would certainly had relevance when it was made. Looking back on it today with what we know now, we find the whole pot of the movie even more futile, being that we know that Venus has a ground surface of 425 degrees celsius, and is covered in poisonous sulphuric clouds, therefore making it impossible for ground-based life to exist there. This fact has been known since about 1963 by the Mariner 2 probe, so why this film chose to ignore this fact and change the story to a jpourney to Mars I do not know. It could be that this knowledge of Venus wasn’t publically known, so the film could get away with it. It could have something to do with more Cold War politics, and keeping this information suppressed out of the public realm. If a movie tried to do this plot nowadays, the general public would probably dismiss it outright as it is widely known (taught in schools even) that Venus is unable to support human life. I guess a remake is out of the question then?

There are a lot of errors, both scientific and continuity are prevalent throughout this film. One of the most obvious ones is that a number of different stock footages are used to show the spaceship Astra which are completely inconsistent. One scene shows a ship that is shaped like a rocket, another is actual degraded footage from a NASA space launch, and in another it is a strange spherical ship that looks like a space station. This confused me quite a bit as I just didn’t know what I was looking at most of the time. There is a lot of techno-babble in this movie too, with some scenes consisting of the crew reading off numbers and values which make no sense. It’s that old cliché that TV shows and movies can get away with making up science because the public will just accept it. In this movie though, the crew just reels off numbers and such for quite a while that it gets very tedious.

The most significant thing about this film is the ending. During the last ten minutes, everything suddenly changes. Due to the film being completed five years after production was halted, the original actors, costumes or sets weren’t available, so at that one point during the movie, it becomes something else entirely. The spacesuits the two crewmembers are in suddenly change appearence completely, and their hemets are coincidentally opaque (To mask the fact that the actors are completely different no doubt). The voices still give it away that they are not the same people, namely the woman seems to have completely lost her Russian accent. Out of nowhere this voice claiming to be the “collective conscious of the population of Venus”, hinted at nowhere in the movie ends the movie with an ambiguous monologue about the mysteries of the universe. It seems to me that the people that bought the movie to make an ending from it wanted to make it have that 2001 vibe, carrying the shuttle off to the distant reaches of the universe. Honestly though, it doesn’t really work on this budget, and not being set up for in the rest of the movie just leaves a sense of bewilderment rather than wonder.

Doomsday Machine is not a movie you would want to watch nowadays. Everything about it is outdated, the production is poor, and the ending makes no sense (in a bad way). The fatalistic events of this movie mean there is nothing feel-good here so you really can’t watch it for a laugh at the bad production. Unless you want to see a prime example of how not to make a movie, this one is a miss for me.